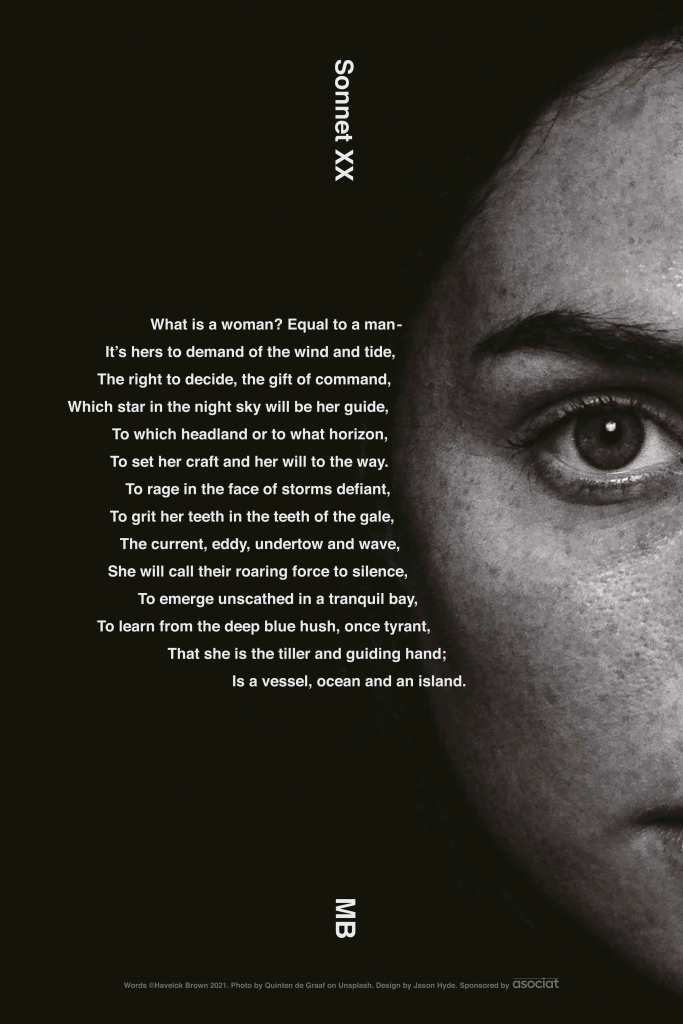

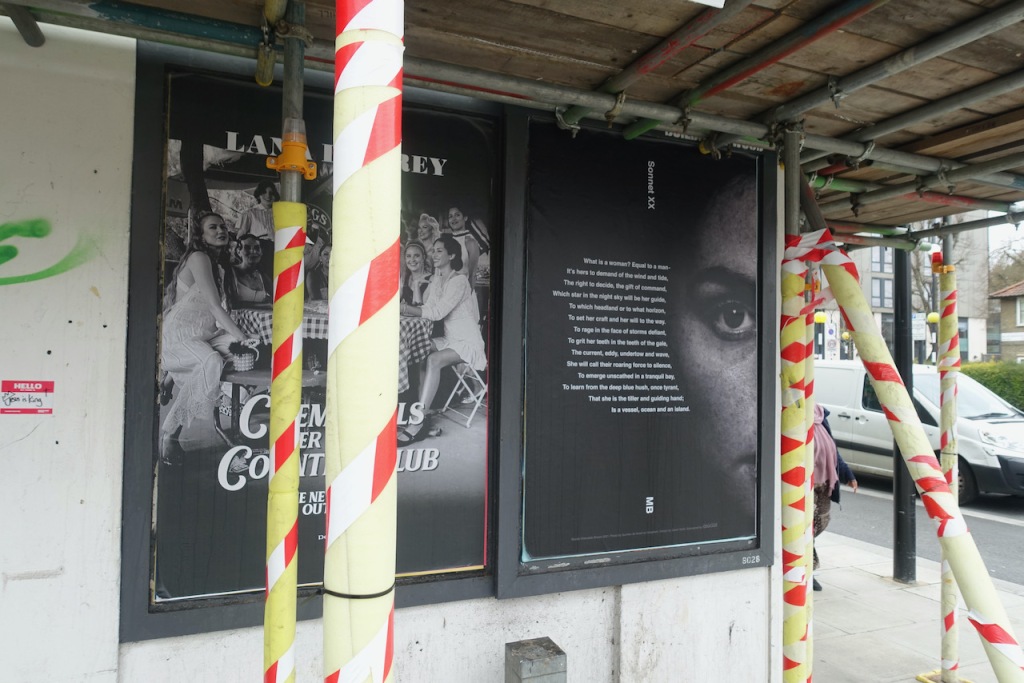

Dangerous territory

As we all know, there have been too many pairs of size 10 Brogues strutting across the topside of the glass ceiling. My line of work is as blighted as any other. In fact it has more to atone for, given past sins in re-enforcing gender stereotypes through innumerable ads.

While the situation is still a long way from being ideal, that glass ceiling is under demolition orders – the wrecking ball is parked outside and there’s a crowd in the car park throwing rocks. Soon there’ll be nothing, save an embarrassed grin, to protect male C-suite executives from the upward gaze of their equally talented female colleagues.

More talented in many cases: A survey of 16,000 leaders by US leadership consultancy Zengar Folkman for Business Insider suggested that women are more effective in business than men. This is just one of several bodies of work from recent history that make similar claims. We’ll come back to the detail later.

I’ve lost count of the amount of people I’ve hired over the years – I’d like to think gender doesn’t influence my judgement. BUT! The research taps into a hunch I’ve harboured for a while: There appears to be some competencies that are more effective in driving down conflict to create a healthier, collaborative, and performance driven business. These competencies manifest more often in women: Dangerous territory, right? Bear with me.

Conflict – why men might be the problem most of the time

It all goes back to some of the areas we’ve covered already such as Darwinism and evolutionary strategy but there’s also a fairly recent discovery; 50% of all humans may have a gene that stimulates an aggressive response to stress and almost all of them will be the proud owners of a penis. Given that stress comes fully baked into the job description for most, I think it’s important for any organisation to take a microscope to biology – to better understand how it impacts day to day culture, and what a manager may be able to do about it. Let’s have a look at the science…

In 2012, Dr Joohyung Lee and Professor Vincent Harley believed they had found the gene that drives men towards aggression when under stress. Predictably it was christened the “Macho Gene’ in news reports; a name that doesn’t quite convey the importance of their discovery. It conjures up an image of a bloke with a genetic tendency to flex his biceps while standing resplendent in budgie smugglers. Perhaps by a swimming pool.

Maybe that’s just me.

The gene is more properly called SRY. Importantly it only appears in the Y Chromosome – which means women don’t possess it.

In utero, the gene triggers the development of the testes and secretes hormones to masculinise the body. If absent, a female foetus develops. This had been thought to be the sole function of SRY until Lee and Harley strapped on their scientific gloves and stepped into the ring. They found that the SRY exists all over the male body; the heart, brain, lungs, kidneys and the adrenal glands – the organ deployed in primary responses to stress. The scientists proposed that the gene therefore plays a role well beyond determining whether a chap will become a chap. It may also drive an exclusively male disposition to come out swinging at times of heightened stress. Or to leg it. A choice known to all, even those who paid scant attention in Biology, as Fight or Flight.

The research supporting Fight/Flight was unveiled to the world by Professor Walter Cannon in 1932. It seems to me that he might have let gender influence his hiring choices; his entire clinical research team may have been entirely male. How else to explain Lee and Harvey’s revelation that almost all the clinical research had been done on men? Gender was not considered when scrutinising the data.

Typical!

All those highly educated blokes and not one of them thought to ask how people with two X chromosomes might react to stress. Turns out it’s different to men.

Conflict resolution – why women might have the answer most of the time

The fact that women don’t have SRY points towards a concurrent conclusion from the world of science: that women’s Fight/Flight instinct is calmed by Tend/Befriend, a process first identified in work by researchers at the University of California in a paper written by Shelley E Taylor pHD and others in 2000.

This paper starts off with a bit of our old friend Darwin; survival depends on the ability to mount a successful response to threat. In antique society that might have been an attack by a hungry predator with particularly large teeth, or a rival tribe with a territorial claim. The theory of natural selection states that innate abilities to successfully counter danger would have a tendency to be passed onto subsequent generations.

According to the Californian paper these abilities may split by gender lines: Fight/Flight fails as a survival strategy for women because historically they have taken primary roles in ensuring the little’uns become the big’uns.

The same Darwinian forces that push men into Fight/Flight works the other way in females: high maternal investment favours threat responses that don’t jeopardise the survival of their children. Reacting in either way, to fight or fly, in the face of that predator for example, puts mum and child at risk and it would not be selected for. Whereas ‘Tending’behaviours involve getting offspring out of the way, calming them down, protecting them from further threat, and anticipating protective measures against dangers that are imminent. ‘Befriending’ activity involves affiliation and collaboration within a group, creating networks to provide mutually assured support during stressful times – -the vital competency of planning for the future. Tend/Befriend means reaching out, building trust and community, defusing conflict, putting the kettle on and breaking out the Rich Teas.

If you consider these descriptors in context of your organisation you might find much to admire – all that collaboration, forward planning and networking are important skills – tend/befriend could be the balm that soothes the conflict.

If I look without any prejudicial squint, I see clear indicators of this behaviour in Balpreet and Sarah; two long term business partners on my management board. Both can engage their inner Boadicea in the hand-to-hand combat sometimes required in business, and in the next breath are elbow-deep creating an induction programme that ensures our newbies have a motivating experience in their first weeks.

In contrast, my past motivations, have often been about competing for and closing of deals – actions exclusively borne of fight mode. Does this indicate that Balpreet and Sarah make a more positive contribution to improving organisational culture than I do?

The research suggests it does:

The tend / befriend instinct and its effect on business and political culture

The 2015 Psychology of Entrepreneurship study by University of Cambridge found that female CEOs generated more profits than their male counterparts. They were more likely to maintain business outlooks favouring controlled growth and reinvesting profits over taking equity out. They were more averse to risks that may mess up their employees’ livelihoods. Men, on the other hand, were more likely to take equity out at the earliest opportunity, taking more risks to do so. Interesting! You might easily identify respective Tend/Befriend versus Fight/Flight behaviours here.

In a related sphere of influence, I’ve been recently reading a UN report in which I see evidence of ‘Tend/Befriend’ qualities driving decisions as to what kind of policies get enacted by female politicians. As one example they report the number of clean drinking water projects in India in areas with women led councils was a massive 62% higher than those with men running the show. Plainly the guys think their constituents need to man up! I mean who needs water, right?

The report describes Norway as a place where the presence of woman on local councils is directly linked to the levels of childcare coverage and legislation.

Does this stray too close to the cliché of female leaders as ‘nurturing’ types?

Returning to the study by US leadership consultancy Zenger Folkman of 16,000 leaders; it suggested women outperformed men in taking initiative, getting things done, and driving for hard results, pointing out that these were ‘not nurturing competencies’ – inferring that they are commonly assumed qualities of male leaders. The United Nations have drawn similar conclusions. Their report contained an introduction which stated there’s established and growing evidence that women’s leadership in political decision-making processes improves them.”

I’m just going to spell that out, underline it and add italics; they mean the outcome of a political situation is better than it would have been if it had been left exclusively to the men.

Is it possible that these so-called ‘male’ business qualities might be smoothed by the fine-grained sandpaper of Tend/Befriend? That women possess a wider spectrum of competencies, and therefore make more rounded leaders? If so, we men clearly need to explore whether or not we can ignore the klaxon call of our testicles and… woman up.

Even the most hawkish of us might concede that there are situations in which that primitive release of chemicals and the response it triggers have not always been helpful – no matter how much fun it might seem to the pugilistic to literally or metaphorically punch your way out of an argument. Knowing when to go with that age-old instinct and recognising when another route is preferential, and having the wherewithal to act upon it, might help improve our relationships.

But where to begin?

How to kickstart a tend/befriend culture

I’ve tried taking a thermostat approach to organisational culture – to gently set the ambient conditions that might allow everyone to begin to channel tend/befriend. A perfect environment to begin to shape this culture is in that staple activity of organisational life – the meeting.

It has been documented by many women in many places, men seem to speak more in meetings. Often speaking over women, and diverting the course of that person’s creative flow, refocusing the room to the interrupter’s ideas – and as has also been commented on to infinity; repackaging ideas expressed earlier by women as their own. It’s my view, and direct experience, that many brilliant trains of thought are ruined in this way.

Not just mine; reams, and reams of research, editorial and comment exist around the negative experience of meetings when viewed through the eyes of women. Google it. No matter which side of this argument you fall, even if your view is that the reported experience of women in meetings is a form of feminist extremism, it needs sorting.

I spoke to Jules Chappell OBE about her experience. When she worked at the Foreign Office, she was posted to Baghdad as a part of the governance team after the fall of Saddam Hussein, where she worked with Iraqi women’s groups, helping a number of female leaders to join the political process in the aftermath of the conflict. She later became the UK’s youngest ambassador. Taking up her post in Guatemala in 2009 at age 31, she made domestic violence a key part of her mission. In both roles, Jules’ duties included the business of conflict resolution. Inevitably, that involved a lot of meetings.

“My single biggest take away from this kind of work is that if you want a negotiation to work, it’s critical to get the first step right – and that’s to get the right people in the room. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve sat through talks in rooms full of men, where clever language was agreed and signed, but ultimately nothing really changed on the ground. I think it makes a big difference if those at the table are more diverse, more representative of the communities involved or actually impacted by the issue.”

Consider the volume of meetings that happen on a daily basis in global organisations. Finding out how many is a tough gig, there have been estimations of between 11 million and 55 million meetings happening daily in the USA alone. Whatever the actual number, it’s safe to assume this is not a minor source of tension. It’s the opposite – a major source of culture warping conflict that’s sustained, endemic and destabilising for 50% of the working population.

Not only that, if the aim of your meeting is to achieve balanced and representative decisions in the quickest time frame possible, then you’re likely to fail if you let the diverters hog all the airtime.

It’s possible to make a few tweaks to the way a meeting is arranged to provide air cover for those besieged tend/befriendtendencies. To allow them to emerge out of the trenches.

| Divert the Diverters: A simple framework for meeting organisers. |

| Ensure your meetings are representative of the population – those gathered round the table are 50/50 split by gender. Think about wider diversity: Companies with diverse workforces are on average more profitable – the logical extension of this is that diversely populated meetings will also be more productive. Diversity Matters by McKinsey found that gender diverse companies where 15 times more likely to be more profitable. Ethnically diverse companies 35 times more likely to be more profitable. Appoint a strong chair who explains the housekeeping in advance:All opinions are valid and welcome. However, if you are inspired by what someone is saying in the meeting, or you immediately hit upon a way to build on it, hold your excitement, don’t blurt it out over the top of the speaker – write it down and wait for the current speaker to stop. Or to be invited in by the chair. We want to get each speaker’s full train of thought – not half of it. If you are the chair: You have the power to call out breaches of the above rule, and to curtail a speaker who wangs on for too long – two minutes is more than enough time – any longer than that and it’s a presentation. Be strong. Your job is to facilitate the transfer of ideas in the room, to ensure those ideas reach their full potential, and make sure everyone is clear on their individual actions arising. Ensure that airtime is shared – invite everyone in the meeting to speak. |

Turning up the heat on the thermostat is a good start. These kinds of tweaks to the rules of a meeting might make everyone feel a little warmer, but a 50/50 split around a meeting room table, or for that matter a board room table, doesn’t necessarily mean a balanced perspective arising from your meeting, or a balanced culture in your organisation.

Nor does it mean equality – which is what we are talking about after all. Achieving this might take a roots and branch upheaval in the male psyche.

Since becoming aware to all this, I’ve actively attempted to identify the moments when my fight/flight behaviours are triggered during the working day, and how that colours my decision making. I have then tried to logically intervene on myself to ask if there might also be a tend/befriend type reaction that may achieve a different result. A thought process which, if I believe the science, puts me into direct conflict with my own body – riddled as it is with SRY! That kind of self-examination has also led me to consider whether or not I can truly unlock the benefits of tend/befriend without overcoming unconscious bias – my own of course.

THE POWER OF CULTURAL NORMS AS A BARRIER TO EQUALITY

Unconscious biases are social stereotypes about certain groups of people that you, me or anyone else can form outside of our own conscious awareness. Unconscious bias is often incompatible with your conscious values – you have to be observant to avoid them having negative effects on your decision making.

Let’s face it, the defining forces of background and upbringing exert a powerful gravitational pull on behaviour. Even more so for those people who may have been raised from a tender age in backgrounds that have been for instance racist; or misogynist; or homophobic; or amongst other antiquated cultural norms that have existed for generations:

Rwanda – a case study

Rwanda holds the record for the highest levels of female representation in parliament in the world; The original impetus for much of this change; the horrific 1994 genocide in which as many as 800,000 Rwandans were killed. 70% of the remaining population where female.

Twenty-five years later, 61% of seats in the Rwandan parliament are held by women. Meanwhile, the global average for women elected into democratic parliaments elsewhere is a paltry 24.1% (March 2020). Public sector jobs also have very healthy gender splits – 50% of judges are female for example. In so many ways, Rwanda is leading the way.

And yet; even if a woman legislates during the day, she must still fold socks by night. These words belong to Susan Thomson, Associate Professor for Peace and Conflict Resolution Studies at Colgate University in New York. She has written extensively on the Rwandan situation since the genocide and has bought to life its complexities in her 2018 book: Rwanda – From Genocide to Precarious Peace.

Thomson told me that she would agree with the generally held view that the ruling RPF party has propelled women to local leadership positions and that this is changing Rwanda’s rural, agrarian economic dimensions. She says there is an opening for true democracy in the future.

There’s also much more to do.

The new society in Rwanda is emerging out of a gender fault line. The professor explains further: Historically, Rwandan women have relied on men. Husbands worked outside the home and made all the important decisions, while wives managed the home front and were financially dependent on men—fathers and brothers before marriage, husbands and their male relatives thereafter. Female survivors of the genocide found that these traditional structures were no longer possible, and they sought changes to reflect the new demographics of post genocide society.

Thomson referred me to the University of Wisconsin political scientist Aili Mari Tripp who has noted that the advancement of women’s rights is a positive by-product of war. Rwanda is no exception. However, like in other post-conflict societies, those men who benefit from traditional gender norms remain resistant to change. Female parliamentarians are expected to do it all—be active public leaders, while also managing domestic life. Rwandan sociologist Justine Uvuza found that the husbands and male relatives of even the most powerful women in Rwandan politics still expected them to do all the household chores. Meanwhile rural women, many of whom are appointed into low-level, female-only positions in government, have only seen their unpaid workloads increase and their economic security threatened as the men in their lives begrudge their presumed influence in society.

The irony is that while some women appear to hold much public cachet, their private lives are still governed by traditional gender expectations.

The presence of prominent women in the public sphere and the possibilities for younger women and girls have come at a cost: domestic violence in Rwanda is at an all-time high. Traditional gender norms of the strong male provider have not caught up with the social and demographic realities of daily life since the genocide ended. According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), one in every three Rwandan women has experienced or continues to suffer violence at the hands of her male relatives.

It’s not just Rwanda

Cases like Rwanda are not unique to the so-called ‘developing world’. Western opinion tends to unthinkingly blame oppression of women squarely at the feet of a widespread unenlightened social, economic and cultural milieu when occurring in countries in the global South, but accepts the same problems as the actions of a handful of individual rogue perpetrators swimming against the tide of enlightenment when occurring in ‘developed world’ economies.

Well, in France, whose state institutionally defines equality, alongside liberty and fraternity as one of its three core values, a woman dies at the hands of her partner once every three days. That figure is almost identical to the UK, and in the US nearly a third of all women have experienced some form of domestic abuse in their lifetimes.

When you hold such statistics up to the light, alongside anti-sexual harassment campaigns such as #MeToo, the shocking realisation is that this is more than just the rogue behaviour of a statistically slim minority of perpetrators – it’s a statistically significant body of men who are responsible.

Defining just how responsible may also be a challenge: There’s the worst sort, and very easy to call out for the harshest opprobrium – that of being an actual predator. Less obvious to some would be the notion that participation in, or even simple tolerance of, lad, bro, or frat culture, even within the restricted confines of an all-male locker room helps to maintain and reinforce wrong thinking entrenched attitudes towards the power balance in male/female relationships.

While no one should seek to apportion blame for their behaviour solely to external factors, the fact remains; the hook of prevailing cultural norms are a difficult barb to wriggle off. Unconscious bias is moulded by these norms and operates as a spectrum, which means it can materialise in extremes such as those horrendous domestic abuse figures. Thankfully, not everyone gathers at the extremes, but one thing’s for sure: Unconscious Bias will affect your thinking to some degree, regardless of background, no matter how educated you become in later life, or how far you travel from your origins. Without exception.

Thinking back to the Norwegian childcare legislation in the UN reports – the men who must have been on those councils did not flex their tend befriend muscles on the days they were engaged in setting policy. Nor where they observant to their own unconscious bias; by overlooking the need for childcare provisions they were simultaneously flagging that they did much less childcare themselves. We might hope that those chaps responsible for inaction would be suitably embarrassed and apologetic should they have ever had their oversight pointed out. I can well imagine myself in such a position, as I can indeed imagine Katy, I’m her husband, pulling me up on it. I’d like to think I’m not an unreconstructed bloke, but I’ve had some reconstruction. Katy and my daughter Millie have been the principle architects.

Unconscious bias training is the commonly accepted way to smooth out the creases on the ironing board of equality…

TWO WAYS TO ACCELERATE THE CHANGE WE NEED

Major investment in order to brush of the grubby paws of unconscious bias from the knees of fairer decision making is already commonplace in many institutions. This is worth a round of applause, but not a standing ovation because it’s usually a one hit wonder. In any educational initiative, consolidation is gained through repetition. Whereas your average person on unconscious bias training is more likely to experience a short one-time only class and would then be left to self-police for the rest of their lives. Years of ingrained cultural behaviour countered in a spare meeting room in sixty minutes – that’s unconscious bias sorted then!

In reality, a training course will help you recognise some of your worst habits, but most of us would need ongoing training to help maintain a state of internal vigilance – to consistently apply your learnings in opposition to your habitual behaviours, assumptions and attitudes– especially if underpinned by evolutionary triggers that split by gender.

Get a drill…

It strikes me that the effects of unconscious bias and outright discrimination, are a health and safety at work issue. True inclusiveness would lead to less conflict and a healthier work environment. A lack of it could contribute to mental health issues, depression and worse.

Attitudes to H&S policies do veer from sneering contempt to grudging appreciation: I once spent an hour I will never be able to retrieve watching a video in which I learned to ascend a step ladder in an open plan office; a skill I’ve never utilised at work ever – I have though mercilessly ridiculed the procedure many times.

Yet there are some things that are so important we plainly need a drill. Think about it. A fire drill consolidates the behaviour most likely to increase everyone’s chances of survival in a conflagration – the necessity to practise this is enshrined into law.

I’m not suggesting you throw on a hi-viz vest and marshal everyone out of the fire exits with a loud hailer each time there’s an unconscious bias transgression, BUT regularly testing your psychological reflexes post training would consolidate learning. The unconscious bias version of a fire drill in corporate life might include experiential learning. Under observation, all levels of seniority could roleplay situations which are known to be heavily skewed by biased preconceptions: job interviews, staff and management meetings, pay performance and promotion reviews. Interventions are staged for those not setting the right tone, and a retraining programme is subsequently devised – all of which is managed under the auspices of the HR function.

Do an Equality Audit

Organisations are legally obliged to co-operate in an annual independent financial audit to prove they are not reporting fraudulently, engaged in money laundering or tax avoidance. Similarly, corporations above an agreed workforce size should be obliged to undergo an annual equality audit to check their culture is compliant to the Equality Act 2010. That rigour exists in their equality measures, protocols and training.

Qualitative interviews with employees would be a key part of the process, particularly those with one or more of the 9 characteristics protected by the act (age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage/civil partnership, pregnancy, race, religion/belief, sex, sexuality).

Who knows, a successful audit might even trigger tax relief – which would add further motivation for business to support the extra level of administration required. In the meantime, until some sunny day when an equality audit is entered into legislation, the only way of doing this would be voluntarily – a bit like self-assessment – which shouldn’t be a problem for any organisation that genuinely wants to change the status quo. I’ve been road testing a 9 question Equality Audit which is very simple to use and provides for a quick pulse check on the status of your organisation.

The test asks questions that require hard-fact black or white answers e.g. does the organisation suffer from a gender pay gap? It either does or it doesn’t. These are mixed with questions which attempt to ascertain the perceptions of people working inside the organisation (particularly those with characteristics protected by the Equality Act).

These perception-based questions are focussed on team engagement and the accepted way to measure that is by asking people if they are proud to be a part of the organisation and further, that they would recommend it as a great place to work –a yes to both those questions are indicators that an individual is ‘engaged’. If for instance women recommend your organisation as a great place to work to other women outside the organisation, then that would be an indicator you were getting some things right.

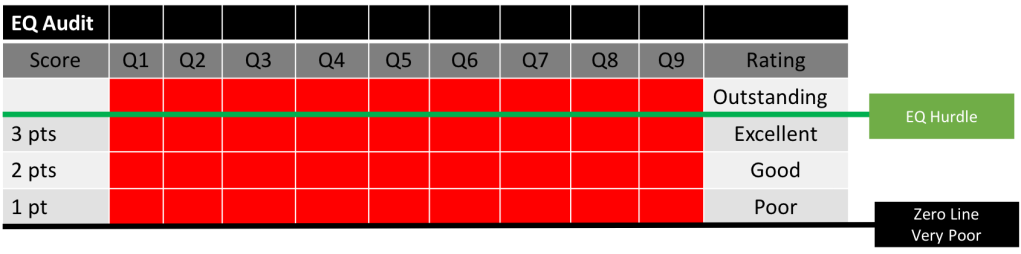

The EQ Audit test – how it works:

The test works a bit like a balance sheet, but on a horizontal plane: Your answers to the questionnaire allow you to plot your progress on the above grid by shading the red boxes in black in accordance with the points you tally – the instructions for how to do this are included on the upcoming question sheet. If every red box under the green hurdle is shaded black then you are in the best place imaginable – to extend the balance sheet metaphor you are literally in credit. In which case the top row will be automatically fully shaded black as a bonus and your organisation will achieve an outstanding rating in this test. Your results will have leapt the green hurdle so to speak.

Most organisations will probably achieve some kind of variation of the below. To note that in this test your organisation does not achieve any kind of ranking until it shades to black every single box in a row e.g. if the row labelled 2 pts is completely black then you are ranked as ‘good’- but you are still in the red as far as the balance sheet goes – you need to get all those boxes in row 3 shaded to leap that hurdle and pass muster on the Equality Audit Test.

I’m not suggesting for a minute that the existence of equality in any organisation can be ascertained through this exercise alone, but as an indication for how your equality measures are perceived, and which areas need to improve, then asking people inside any organisation for their view is a good place to start – perception is everything.

INSERT TEST

| Question 1. Does your organisation have a gender pay gap (men are paid higher than women for the same role)? | Score |

| Yes: 0 points | |

| No: 3 points | |

| If Yes; Has there been an announcement from the senior leadership to its employees about the measures that will be taken to ensure gender pay parity? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No: 0 points | |

| If Yes; Has a hard deadline been announced within which equal pay will be achieved? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Question 2. What is the gender split of the C-suite / senior leadership? (Use rounding up /down). | |

| 50/50 split: 3 points | |

| 60M/40F split: 2 points | |

| 70M/30F split: 1 point | |

| Any higher than 70% Male: 0 points | |

| Question 3. Is BAME and LGBT diversity amongst senior leadership representative of the population (of the country/location your company is based in). | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Are members of the BAME community visible as role models in senior leadership ? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Are members of the LGBT community visible as role models in senior leadership ? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Question 4. Does the organisation pay contractual maternity pay (as opposed to the legal minimum of statutory maternity pay)? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Do your working parents agree that the organisation is flexible & accommodating around their childcare requirements after returning to work? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 points | |

| Do your working parents agree that having children has NOT held them back in their career inside this organisation? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Question 5. Is the organisation’s environment set up so that physically impaired people have means off access ? (Your building must have toilets, ramps and lifts to score a point in this question). | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Is the organisation’s environment set up so that sensory impaired people are catered for? (Your building must have aural enhancement loops, colour contrast in signage and good lighting to score a point in this question. (If you don’t know the answer to this, the answer is no) | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Does the organisation run or endorse a help line or support such as access to counselling for people with mental health issues? (If you don’t know the answer to this, the answer is no) | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Question 6. As a member of our BAME community, are you proud to say you work here? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| As a member of our BAME community would you recommend this organisation as a great place for other BAME people to work? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| If you have scored two Yes answers in Q6 add a bonus point here: | |

| Question 7. As a member of our LGBT community, are you proud to say that you work here? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| As a member of our LGBT community would you recommend this organisation as a great place for other LGBT people to work? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| If you have scored two Yes answers in Q7 add a bonus point here: | |

| Question 8. As a working parent, are you proud to say that you work here? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| As a working parent would you recommend this organisation as a great place for other working parents to work? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| If you have scored 2 Yes answers in Q8 add a bonus point here: | |

| Question 9. Do you think that age is a barrier to success inside this organisation? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Do you think that holding strong political or religious beliefs is a barrier to success inside this organisation? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point | |

| Do you think that being female is a barrier to success inside this organisation? | |

| Yes: 1 point | |

| No : 0 point |

*I should note that the above questionnaire is aimed at people who are involved in the running of organisations, large departments and teams. Questions 6 to 9 require access to the knowledge the organisation owns about everyone who works in it. I have assumed these team engagement enquiries have already been asked in previous employee research by the HR function, and the results are known. However any individual can sense check the organisation in which they work by answering the hard fact questions (1 to 5) as these are easily accessible public-knowledge, and then in questions 6, 7 and 8 simply ask the two engagement questions of just one colleague in each of the communities covered. I would argue that a negative engagement response by just one member of any community member protected by the equality act suggests a wider problem inside the organisation – no one person should get left behind. Answer the first two questions in number 9 yourself, and if you’re not female, ask your female colleagues the last one.

Woman Up – why know?

This chapter started with the research concerning the Fight/Flight instinct and the effects of the SRY gene in the male body – It asked whether or not men can intellectually counter the effects of both and how this might help create better organisational culture by nurturing a tend/befriend outlook. The research suggests this is the default position of women in high stress situations and may confer many advantages, not the least of which is more collaboration and more harmony.

Tantalisingly, the Zenger Folkman study ranked gender against 16 competencies deemed essential to success, including communicating prolifically, developing others and being collaborative (women came out top in 12). To describe these qualities as competencies is important, because a competency is a learned thing. I may be hardwired to fight or flight, but I can cling to the idea that, with practice, I could become a tenderer befriender. It’s this quality that will also help take on the insidious effects of unconscious bias and combat the worst cultural norms.

Annie Rickard, former global president of out-of-home media company Posterscope (and ex-boss, business partner and mentor of mine) once told me that she would know we’ve reached equality when there are as many mediocre women running companies as there are mediocre men. Many high achieving women, like Annie, feel they’ve had to work so much harder than men to get to the same place.

Inequality is holding business, politics and culture back. It’s probably the last great source of conflict in the world and the most important collaboration project we might embark on. Men and women aren’t from different planets – we’re the same species. We don’t need to be sat in opposing camps. The unique demands of our time obligate us all to flex those tend/befriend muscles. To achieve this, we need all the talent in the world, working in harmony from a position of jointly held power. Let’s get on with it: woman up.

Get 25% off retail price and free UK postage when you order I Don’t Agree at the publishers site using IWD25 at checkout here…

If you would like a PDF version of Step 5: Woman Up, please email us using this form…